How Tight Labor Markets Impact Pay Equity

An unprecedented five years have unfolded in the labor markets, reflected by surges in retirements, career transitions, and remote work arrangements. The supply and demand for talent were incredibly misaligned from 2020 to 2022. During 2021 and 2022, the time known as the Great Resignation, starting salaries spiked. Retention bonuses, out-of-cycle promotions, and opportunities for remote work became commonplace.

Then, starting in late 2022, the labor market cooled. Some businesses pulled back on hiring more than others. But even in hard-hit sectors like technology, the demand for certain skills (like AI) hasn’t subsided at all.

All this change has only made it tougher to get in front of the already-complex issue of pay equity.

The idea of pay equity—equal pay for substantially similar work—is simple. Making it happen, not so much, especially when the labor market goes through an unprecedented transformation. Compensation committees, CEOs, and CHROs expect to see evidence of perfect pay equity or a steady improvement in progress. But what happens when there’s a secular shock in the broader labor market that throws the results into disequilibrium?

In this article, we’ll use a hypothetical example to show how common responses to broader labor market issues can unintentionally create disparities in pay. Then we’ll lay out some common strategies for mitigating the pay equity challenges that arise in the race to keep key positions filled.

We’ll work through the top flavors of labor shocks our pay equity clients have experienced and what those can do to a pay equity management program. Some companies had one type of shock, others were hit with multiple.

Compensation committees of course want to see progress toward perfect pay equity, but they’re also interested in the overall story. They need to understand what’s happening in the talent pool, any setbacks the company is dealing with, and what the company is doing to remediate disparities. A best-in-class pay equity monitoring program acknowledges all of these issues. We’ll take the same approach to our discussion here.

Shock 1: High Velocity Employee Entry and Exit

The Great Resignation led to unprecedented levels of attrition and new employee acquisition efforts. As more workers leave, the pressure to replace them and manage burnout among remaining employees goes up. This in turn leads to aggressive negotiating, paying beyond the market range, relaxing prior experience requirements, and making concessions on work location. All these real-world dynamics can substantially impact pay equity in the organization.

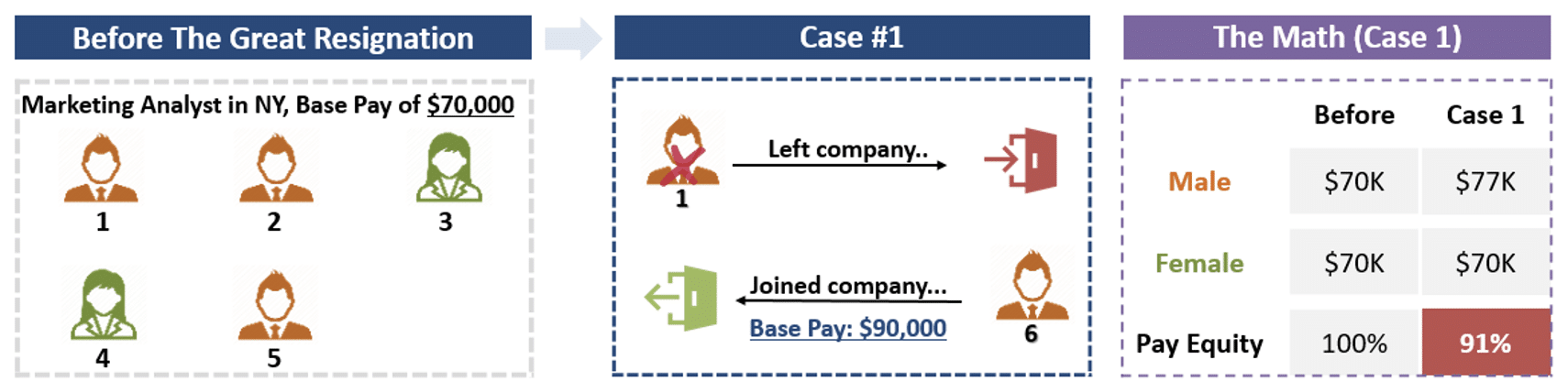

Consider a hypothetical example of three men and two women in the same role at a company, as shown in Figure 1 below. The five work at the company’s New York office with a base pay of $70,000. For simplicity, assume they all have similar work experience, and all other factors contributing to their pay are the same. At this point, the male and female average pay is $70,000, which results in a perfect gender-based pay parity of 100%.

Then employee 1, a man, leaves and is replaced by another man. Due to the tight labor market and rapidly escalating market rates for pay, base pay for the new hire is $90,000. While the new employees was hired with a higher pay, the pay of the existing tenured employees was not adjusted to the new market normal . All else equal, this increases the male average pay to $77,000, while the female average pay remains at $70,000. This in turn reduces the gender pay parity from 100% to 91% (i.e., on average, female employees earn 91% that of their male colleagues in the same role).

If the company hired a woman at $90,000 instead, the result would still be a gender-based pay gap, albeit one that favored female employees.

What’s troubling about this hypothetical is that the company is fastidiously adhering to its compensation philosophy and avoiding one-off negotiations that may be subject to bias. The pay gap is widening anyway, solely due to entry and exit amid quickly rising rates of pay. The company could adjust all existing employees commensurately, but it would need to have the budget for this and synchronize it with merit adjustments.

This is a simple scenario. But if it played out across multiple departments, business units, and hiring managers, it could undo years of progress toward pay equity. The first step in managing the issue is to analyze HR data for potential root causes. For example:

- Is the rate of turnover higher among a certain gender or race? If so, why? How does the gender and race balance of new entrants compare with that of the incumbent cohort? If it’s different, then the mere inflow and outflow of talent amid changing compensation levels will impact pay equity results.

- Is there an internal pay range for each role? If so, where in the range are the new hires coming in? Are they getting hired at the upper end of the range?

- How does the pay of new hires compare with that of existing employees? Have merit adjustments for existing employees kept up with new hire offer letter bands?

- Is prior work experience deprioritized when hiring? Is the company hiring new employees with relatively less experience at higher pay? What other factors are impacting pay, and are they being treated the same for new and existing employees?

- Are a lot of negotiations happening at the hiring stage? Does a particular gender or race seem to be negotiating harder?

These questions have empirical answers. Testing them can help you determine whether the situation is improving. It can also help you decide whether the solution is to make operational changes to the job architecture or banding system, or whether the pay equity regression model needs to be adapted to incorporate the new activity. For example, there’s nothing precluding a decision to relax experience requirements when trying to fill positions during a tight labor market. However, if this is the decision (explicitly or implicitly), then the pay equity regression framework needs to be adapted accordingly.

Finally, enabling real-time comparisons of new hire offers against pay for existing employees can help you flag potential pay inequities earlier. We’ve developed tools that test new hire offer letters against the pay equity framework to keep those offers from worsening existing gaps. But these tools need custom regression models and regular updating to reflect current labor market dynamics.

**************

Pay Compression and Pay Inversion

Are new hires with much less experience making almost as much as current employees who have more experience or tenure with the company? That’s pay compression in action. Pay compression can become pay inversion when new hires with less experience earn more than tenured or more experienced employees.

Usually, pay compression and pay inversion are separate issues from gender or racial pay equity, but they have a startling way of intersecting. Think about situations in which new hires are predominantly men. Their entry spells higher relative pay versus the existing cohort who is generally more “stuck” at prior pay levels. Suddenly, pay compression and pay inversion—delicate topics by themselves—become engines for widening pay equity gaps.

A pay compression study can help you understand how each incremental year of experience affects employee pay. This will also inform decisions about how to update the pay equity regression frameworks to handle the structural changes to pay levels.

**************

Shock 2: Intra-Cohort Retention Pay and Mobility

Unsurprisingly, there was an uptick in special retention bonuses to retain key talent. These bonuses help to manage turnover, at least in the short term. However, ad hoc retention bonuses are very much a discretionary pay decision, which could have pay equity implications. With the Great Resignation wound down in 2023, the velocity of such activity is also down, but these decisions live on in a company’s data and require a perspective on how to handle them.

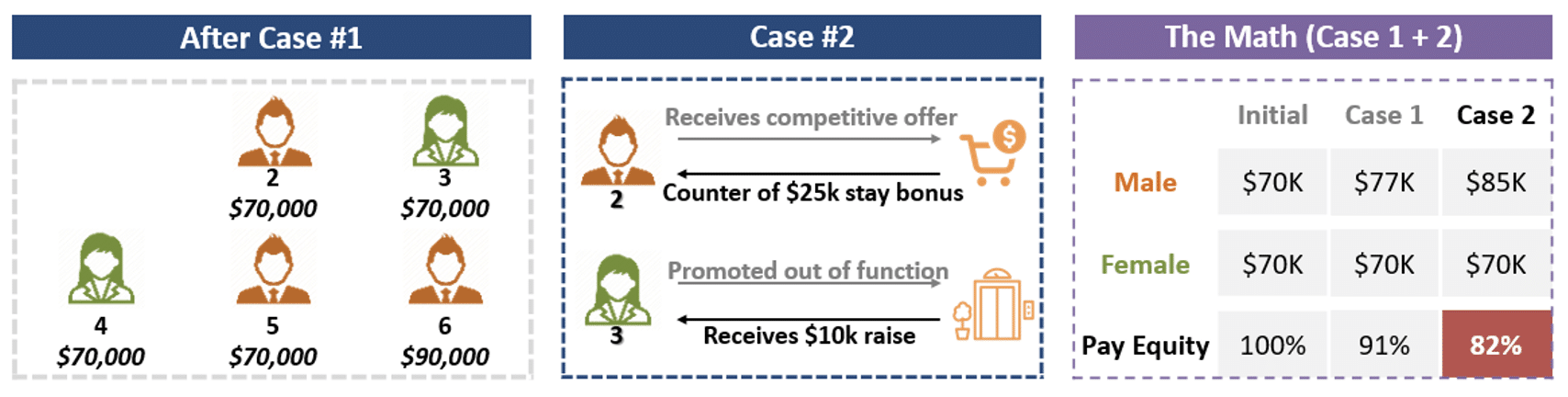

Let’s continue with our hypothetical example from earlier.

When we left our cohort of New York employees, it included two men and two women each earning $70,000, plus one man earning $90,000. Now employee 2, one of the men earning $70,000, receives a competitive job offer and asks his manager to match it. Instead, the company decides to offer a $25,000 special retention bonus. That convinces employee 2 to stay. As a result, average pay for men in the cohort rises to $85,000.

This example shows why retention bonuses should generally be considered when assessing pay equity, even though they don’t change base pay. An important technical question is how and whether to incorporate retention bonuses into pay equity models (which is another reason to avoid off-the-shelf tools).

Coming back to our example, employee 3, a woman, indicates she’s actively interviewing for other jobs. The company responds with an out-of-cycle promotion that comes with a $10,000 base pay raise. Although employee 3 is now earning more, her promotion to a different role means that average pay for women in the cohort she just exited remains at $70,000, thereby reducing gender pay parity to 82%.

Different approaches are reasonable in a situation like this, and our polling suggests the broader market also adopts different viewpoints. For example, some companies may choose to leave employee 3 in her prior cohort for the pay equity analysis because she’s too new to the cohort she was promoted into. Some companies choose to exclude one-time retention bonuses from their core pay equity study and test these for bias separately. Other companies aspire to include all dimensions of pay in their core pay equity model. These are important decision points that should be worked through among the project team.

Shock 3: Remote Work

No post-COVID discussion on human capital would be complete without addressing the impact of remote work.

Some companies adjust pay based on the individual’s location. In such cases, location may be a valid factor that can explain pay differences under the specific legal context. To make this more tangible, let’s go back to our hypothetical example.

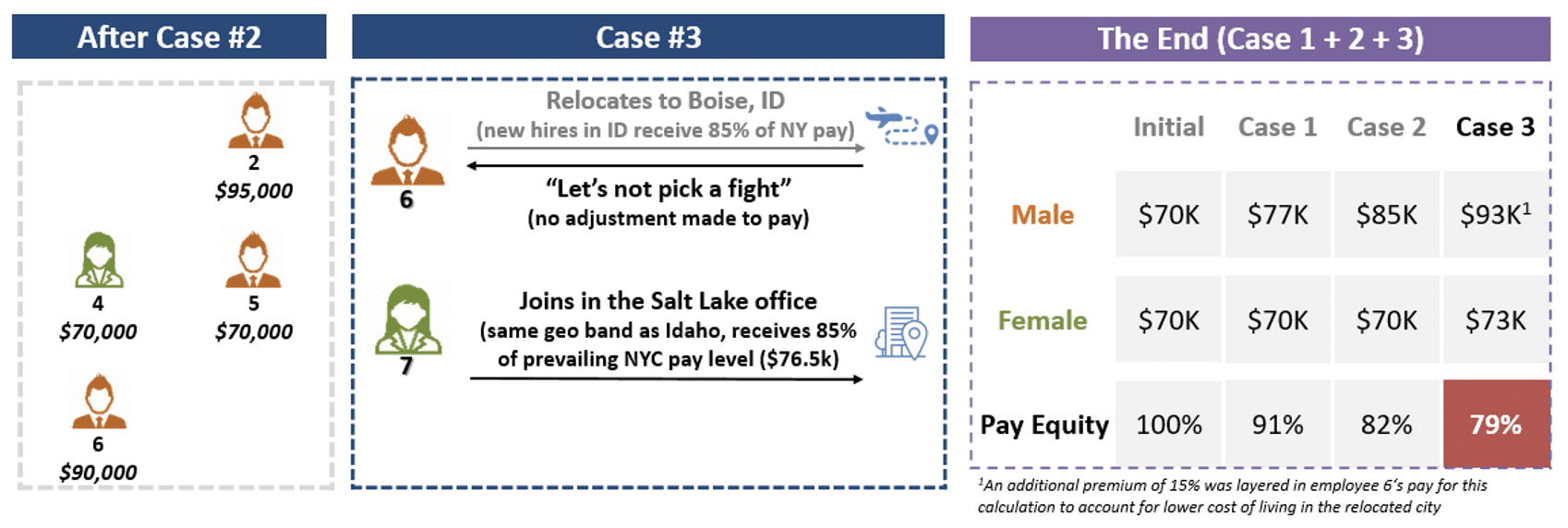

Recall that employee 1 is long gone, employee 2 negotiated a raise, and employee 3 got promoted and left the cohort. To replace employee 3, the company hires employee 6 at $90,000. Then employee 6 tires of New York. To keep him on board, the company agrees to let him work remotely from Boise, Idaho.

The company believes in varying pay based on cost-of-living differences. Ordinarily, any new employee in Boise would be paid 15% less than an employee in New York. But employee 6 relocated and the company doesn’t yet have a policy on whether and how to adjust pay due to employee relocation. So the company allows employee 6 to retain his New York salary for the time being.

Around the same time, the company hires a new employee to join its Salt Lake office and decides to pay that employee 85% of the New York pay. Note that the company’s salary for this role is now at $90,000 (as Employee 6 was hired at this amount). However, none of the other employees in the role received a pay adjustment because the company’s annual merit cycle hasn’t yet occurred and, even so, average merit adjustments were slated to fall below the percentage increase in new hire salaries versus a year prior.

Notice that the company’s philosophy says that location does matter in influencing pay and the company would pay a Boise or Salt Lake City employee differently from a New York employee. But the company chose to suspend its philosophy with employee 6 and let him keep his New York salary while living in Boise, therefore building an invisible 15% premium to employee 6’s pay.

The quantitative impact on pay equity is straightforward—it goes down from 82% to 79%. However, there’s a broader issue related to pay adjustments for workers who relocate to a lower-cost area. The lack of clear policies and guidelines on this topic creates high levels of discretion between employees and managers, which could become a source of pay inequities.

The first step in tackling this issue is for companies to have a clear and well-defined position on the impact of location on pay. (This is often easier said than done.) If geographic mobility does make sense, it’s important for the company to keep track of it so that compensation decisions can be consistently applied and this factor layered into a pay equity study.

One solution is to update the pay equity model so that legacy hires are granted waivers from location-based pay adjustments. A pay equity regression model can quantitatively make these accommodations. However, the company needs to update the model accordingly and test it to ensure such exceptions are not being granted in a biased manner.

Crafting Strategies

As we’ve shown, companies can take numerous actions to manage hiring and turnover in a tight labor market, which in turn can create unintended consequences for pay equity within the organization. Although specific strategies to address the issue should reflect the company’s facts and circumstances, here are some common areas to consider.

Job structure and leveling. In a pay equity study, we analyze the pay of employees doing substantially similar jobs. A robust internal job architecture makes it easier to identify employees that perform comparable work, drill down to root causes, and glean meaningful insights. However, the priorities that the job architecture framework supports may not match the statistical priorities involved in running a pay equity analysis.

We often implement additional cohort groupings in our pay equity projects to balance the regression models’ need for hefty sample sizes without blurring the lines between job types and roles. This is to avoid the inappropriate groupings that mass-market software may produce.

Regression model retrofitting. As we’ve discussed elsewhere, pay equity regression models are supposed to help explain reality. That means they should reflect changes in the company’s context (i.e., how it’s making decisions and responding to shifts in the labor market). This is immensely important in how we approach annual pay equity studies.

Hiring and retention. It’s critical to have well-defined guidelines and policies for negotiating pay with job candidates. Too much discretion can give rise to pay inequities. Even if guidelines exist, exceptions need to be tightly monitored lest every case become an exception. The process needs to accommodate the business realities on the ground while guarding against gender or race-linked exception handling.

In a hot labor market, it can be helpful to deploy real-time tools to test new hire pay and negotiation tolerance by layering in market benchmarking data and results from the pay equity study.

Performance analysis and pay. Merit cycles, performance analyses, and promotions are tricky. Companies are often surprised to discover that gender or racial differences create different pay outcomes despite similar performance levels. One reason this can happen is pay negotiation. According to one study, women are just as likely as men to negotiate, but less likely to get what they ask for. Even small differences of this nature can add up to a significant gender pay gap over time, especially if the company bases future year increases on the prior year’s salary.

A pay equity study can assist by studying employees’ journeys over time and identifying whether inequities arose from the start or emerged some number of years later post-hire. These side analytics can be extremely helpful in identifying root causes and areas for further investigation.

Establishing comprehensive equity. Equity in compensation is just one facet of overall equitable practices within the organization. It can also be hard to separate equitable pay from equitable hiring or promotion.[1] For these reasons, consider studying equity from multiple perspectives using statistical tools like logistic regression.

Pay equity is a journey, with quantitative statistical modeling just the first step. The aim is to make changes based on the analysis and monitor the results over time to see whether the numbers are moving in the right direction. However, even perfectly crafted and data-based remediation strategies will need to be dynamic amid a tight labor market. In these situations, progress in pay equity rests on a company’s ability to use the available data properly and pivot strategies quickly.

[1] To understand why, suppose an organization’s manager cohort is compared with the senior manager cohort. On the surface, there doesn’t appear to be any pay inequity based on gender. But further examination reveals that a number of women in the manager cohort are well past due to get promoted to senior manager. Therefore, the absence of pay inequity could be the result of promotion inequity.